The life of most humans is riddled with regrets, remorse, things we’d rather forget about and stuff that was just plain embarrassing. To this extent, I used to be a trainspotter.

In fact, I still am a trainspotter. It’s not something you can shake off, like chicken pox or a heroin addiction. Trainspotting is like herpes, with none of the physical blemishes, but with all the social rejection. Before Danny Boyle and Ewan McGregor made trainspotting a watchword for urban cool, I used to spend many a Saturday in the late 1980s standing at the far end of the platform at Manchester Piccadilly or England’s less pretty towns—Doncaster, Grantham, Crewe—watching the trains coming in and out of the station and writing down the numbers of all the locomotives and multiple units I saw. Then I would go home and tick off those numbers in three small pocket-sized picture books containing all the numbers of all the locomotives, diesel multiple units and electric multiple units on the British Rail network. This is basically what trainspotting consists off, and very satisfying is it too. There were (probably still are) also books containing all the numbers of all the carriages on the British Rail network, for those people who spotted carriages (weirdoes), and books with all the orange buses in the Greater Manchester Passenger Transport Executive, for those who spotted buses (even weirder—who cares about buses?)

Trainspotting used to be something every British schoolboy did, back in the day. Then, some time in the 1960s, something happened—diesel traction, the pill, the chord at the start of ‘A Hard Day’s Night’, who knows—and nearly every schoolboy stopped spending his weekends trying to see every train in Britain and found something more worthwhile to do with his time, though who knows what that could be. Trainspotting became the preserve of boys and men in bad spectacles (not so much National Health—too cool for us—but rather the kind of rounded square metal frames that you imagine going quite well with tinted yellow lenses and a moustache and a criminal record) and dark blue, unbranded quilted, hooded coats (one rarely saw the classic fur-lined anorak, which again, would have been too cool; we merely wore the first thing our mothers found in BHS) who took scant interest in their personal presentation, had little experience of friendship and even less experience with the opposite sex. Trainspotting was, in short, the ideal pastime for adolescent me.

My trainspotting days of approximately 1987-90 were adventurous times. I broke my glasses at Sheffield station, running to catch the connecting train to Doncaster, falling on the stairs and watching them bounce down the steps before me, the lenses shattering and robbing me of the very eyesight I needed for a day of trainspotting. My friend Stuart had to read out the train numbers to me. I felt like I was cheating.

We were heading for Doncaster because it was the nearest station on the East Coast Main Line, and therefore prime Class 91 spotting country. The Class 91s were the new high-speed replacements for the Class 43s, or Inter City 125 Haitch Ess Tees as you laymen called them, and how I despised you for it. They were sleek and sexy and made our own West Coast Main Line’s Class 90s look tawdry and second-best.

I saw my first Class 91 before it even came into service, when the locomotive was being tested at Grantham station. I’d go and stay with my Nanna Clare in Grantham for a week in the school holidays and she’d drop me at the station while she did her shopping in Morrison’s in the Sir Isaac Newton Shopping Centre, which had a decorative clock with an apple that fell every fifteen minutes onto a blinking lion. That was when I saw her, looking futuristic and mysterious in the rare sunshine (the train, not my gran), a thing heretofore never beheld in the annals of trainspotting lore. Few moments in my early adolescence compare to the day I saw my first spanking new Class 91. Now they look outdated and pointy in a late-80s kind of way, like when you see a tramp sleeping in a Ford Sierra or Austin Montego and remember how that used to be the kind of car owned by families richer than yours.

Stuart Wilks, my companion on many of these trips, was nerdy like me, and enjoyed nothing more than railway modelling in his spare time. But although Stuart spent his weekends building a scale model of an imaginary British railway station, delicately painting shoe polish onto his Hornby Class 31 to give it that authentic ‘weathered’ look, he did not consider himself a trainspotter, and believed that he occupied some superior plain to me, because he didn’t write down the numbers of the trains he went out of his way to see. In retrospect, his ‘train-watching’ hobby was even more pointless than mine, since at least mine had a very real and useful point to it, which was to see every train in the country and write down their numbers, and if there was a finer purpose to life I had yet to find it.

It should be noted, if it has not already been presumed, that in the eyes of Stockport’s teenage girls, the pubescent me was not considered a ‘catch’. Far from it. I side-parted my hair with a careful comb. I wore the large, metal-framed spectacles of a forty-year-old accountant. There were scant opportunities for meeting likeminded women in the world of trainspotting, a world that is male-dominated without being particularly masculine, if you see what I mean. (It is my understanding that women did not begin to openly undertake nerdy activities—going to Trekkie conventions, listening to Rush, using ugly glasses on purpose— until the mid 1990s.) I only once saw a woman trainspotter, at that trainspotters’ haven that is Crewe. It was pretty surprising. Then another trainspotter came over and expressed how surprised he was to see not one but two women trainspotters on the same day. I looked down the platform, looking for this second woman. There was no second woman. He thought I was a girl.

I had had one nominal girlfriend who, three months into our courtship, leaned away from me on the one occasion I got up the nerve to kiss her cheek. Her name was Adele. I dumped her shortly after through the medium of her friend Rachel, which medium had in fact served for all courting and communicational aspects of this frigid fling. Rachel said Adele wanted to know if we could still be friends. I acquiesced with grace.

Then in the summer of 1990, something happened that, incredibly, surpassed my Class 91 moment. On a French exchange trip to Béziers, I kissed a girl for the first time, properly, you know, with tongues and everything (the tongue came as a huge surprise; I had no idea that was what my peers had been doing all this time with their mouths clamped over each others’, and now understood why they spent so long doing it), at the embarrassingly late age of fourteen, and discovered that there was, after all, a far finer purpose to life than writing down train numbers on a windy platform in Cheshire, causing gender confusion in passers-by. Within a month of returning to England I had dismantled my model railway, sold the rolling stock and put away these childish things, for fear that news of my habits would reach southern France.

If only trainspotting were that easy to leave behind. Ever since then, I’ve craned my neck whenever passing a shunting yard or level crossing. I’ve glanced and swallowed at the railway magazines on newsagent’s racks like others glance and swallow at rhythm mags. I’ve often found myself at a loose end in front of a computer and surreptitiously searched for photos of Class 47s in Rail Blue livery, or videos of other people’s heartbreakingly realistic model railways on YouTube. I’ve perused model railway equipment prices and been resoundingly discouraged from returning down that particular avenue. But the real trains were still out there, albeit dwindling in number, and my urge to take them, to see them, to be among them —to be in them— for no particular reason or purpose remained ever strong. I didn’t choose to write this book. I was always predestined to write it.

I moved to Argentina in 1999. Before I started writing this book in March 2013, I had taken very few trains in Argentina in the preceding fourteen years: the San Martín from Palermo to Retiro, as a kind of ‘do trains really exist in Argentina, and if so, what are they like?’ experiment; the Urquiza between Lacroze and Villa Devoto to teach an English class so boring that I once fell asleep during it; Constitución to Lomas de Zamora to examine First Certificate candidates; the Mitre from Belgrano C to Tigre and from Belgrano R to Retiro, both several times; and most of the Subte, though some parts of it far more than others. I find this list disconcertingly short, and yet it’s probably quite average for most of those who live in Buenos Aires and its environs.

My decision to write this book came in the week that the Vatican, in its eternal wisdom, decided to put an Argentine in charge of international Catholicism, and I was feeling oddly patriotic towards my adopted country, although I should stress that the papacy and patriotism are not ordinarily concepts that motivate me. I was in a parrilla in San Telmo with some ex-pat friends, looking for a new book to write. I mentioned the idea of writing a book about taking all the trains in Argentina. One friend wondered whether there were enough trains in Argentina to write any more than a pamphlet. I had my doubts.

The Argentine railway system used to be the biggest in the southern hemisphere, although do bear in mind there aren’t that many of us down here, you only have to beat Brazil and Australia and the hemispherical crown is pretty much yours. Nonetheless, it was a big ‘un. Tens of thousands of miles stretching to every province in the country, mostly built by the British in what was a fine bit of century-long conniving between a succession of easily-swayed Argentine governments and cock-sure British imperialists, although the French and the Belgians also did their bit, because that’s how imperialism works (go and have a look at the old Avellaneda station on the defunct Ferrocarril Provincial, when you can; there’s no way the British built that, it’s too fancy.)

The railways were nationalized by notorious Anglophile Juan Domingo Perón in 1948, by which time they’d deteriorated a certain amount because the British were too busy with the unravelling of the inter-war economy and a spot of bother on the continent to do much more than leach money out of them. Post-nationalization, the railways grew again to a peak of some 47,059 kilometres of track in 1960, which is the year of the railway map various Argentines show other Argentines to depress them about how great this country used to be, at least in that respect (it still is great in many other respects: Mirta Legrand is in her eightieth year of hosting televised lunches; the country has one of the world’s highest barbecue per capita ratios; great importance is placed on sitting round chatting while sharing a hot infusion.) Then basically Argentina did the same that most other countries with any sizeable railway did, which was to dick about with it. With the growth of private motor transport, governments started to ask themselves ‘What do we need all these old railways for?’ Britain’s Beeching cuts in the 1960s did away with about a third of her railways, while in Argentina the World Bank’s 1961 Larkin Plan sought to do likewise. A major strike—you can always rely on Argentines to go on strike—and other factors prevented the plan, which as far as plans go was pretty terrible, from being carried out in full, but Argentina still haemorrhaged four branch lines and a fair number of staff. Things improved with new and much needed trains in the late 60s and early 70s, while the whole operation was renamed Ferrocarriles Argentinos and given one of the coolest logos in the world, complete with greyhound, just so you knew how fast it was. The Buenos Aires-Tucumán Express ran for the first time in 1969, one of the most luxurious trains in the world, covering 660 miles in a mere fifteen hours, almost twice as fast as the same service in 2014.

If there was one thing the military government of 1976-83 hated more than long-haired Peronist hippies, it was trains, and they set about not only cancelling services but also ripping up the tracks so that trains would never run again. By March 1976, Argentina still had 41,463 kilometres of railways. The military government axed that down to 23,923 in the space of seven years. So although the former president they call ‘Carlos Saúl’ or ‘The Devil’, or various other names because his surname is supposedly jinxed, is often blamed for destroying the railways, there wasn’t all that much left to destroy. He did his worst, though, when on 10 March 1993, the man with the disco sideburns brought an end to pleasant habit of travelling long distances by train, leaving it up to the fiscally-limited provinces to keep any trains running. Very few could. Twenty years of further railway neglect post-privatization ensued, culminating in the 2012 Once rail crash, in which fifty-one people were killed when a train went through the buffers at this Buenos Aires terminus. Surely, after so much carnage, there couldn’t possibly be enough trains left in Argentina for a book?

I went home and looked for a map of the Argentine passenger system. It was bigger than I, and perhaps any other non-expert local might have expected. The website sateliteferroviario.com.ar (it speaks volumes that the most complete website with Argentine train times and information is a fellow rail enthusiast’s labour of love rather than a site run by the government or the railway operators) listed, in March 2013, about seventy different rail services: long-distance trains to Tucumán, Córdoba, Rosario; to Junín, Bahía Blanca, Mar del Plata, Tandil, General Alvear, Realicó; the Tren Patagónico across Rio Negro from Viedma to Bariloche; the less famous or desirable nameless train across Entre Ríos from Paraná to Concepción del Uruguay; three local to medium-distance trains in El Chaco and another in Salta; a tram in Mendoza; the Train to the Clouds, the Train at the End of the World, a couple of narrow-gauge Patagonian steam trains calling themselves La Trochita (the narrow gauge Old Patagonian Express); plus the great mass of local trains serving Greater Buenos Aires, the six Subte (underground) lines, the Premetro, and that absurd little tram in Caballito.

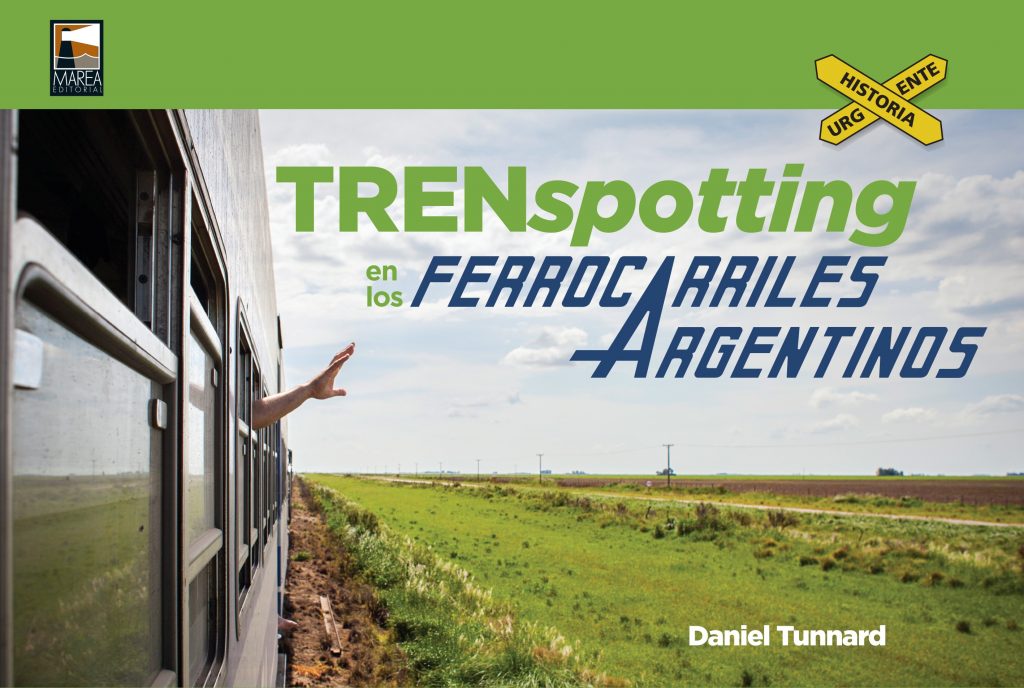

I started writing this book with the idea of taking everything that runs on rails in Argentina and doing things in each place I visited that I considered to be typically Argentine without being stereotypically Argentine, if you see what I mean. This went well for about the first eight months. Then I started to not take trains. I didn’t take a ten-kilometre-long branch to Gutiérrez, because there was nothing there. I took the train to Tandil, and then months later they started up a tourist train between Tandil and Vela. I was hardly going to take the trouble to go all the way back to Tandil to take that. I took the train to La Plata and then months later they started up the Tren Universitario across the city. If I couldn’t be bothered to go back to lovely Tandil, I certainly couldn’t be bothered to go back to La Plata. I took the train to Córdoba and didn’t take the line from there to Villa María, since it’s the same line that goes to Buenos Aires anyway and I couldn’t find reasonably priced accommodation in Villa María because of a folk festival of surprising popularity, and besides, it’s a terribly boring journey through endless fields of soy, and after a year I was beginning to realise that there wasn’t so much to say about so much monotony. In fact, although a lot of people imagine that there must be great views to be had from taking trains all over Argentina, this being a country that, for all its woes, does at least have some stunning views to salvage national pride, almost all the journeys were like the Córdoba to Villa María line, hours passing slowly through the monotony of a field of some kind of cereal, and after a year I started to realise that I didn’t have much to say about so much monotony, although one thing you can say is that there aren’t many experiences quite so Argentine as a long journey across endless fields. I decided that instead of writing a very long and monotonous book about the boredom and expense of taking all the trains in the country, I’d write this book, which is a really quite super book about Argentine trains and kind of about Argentina in general, written by someone who really likes Argentine trains and Argentina in general.

It was a combination of those elementary Argentine traits—informality, affability, generosity—that meant I finally got to ride in a locomotive, eighteen months after starting this project and some twenty-four years after putting away such trainspotter dreams.

It was 3am at a quaint early-twentieth-century British-built country railway station in the middle of nowhere. Most of the railway stations in this book are like this. My attempts at sleep had floundered on hard seats and bright lights. I got off for a smoke on the platform, where a railway enthusiast called Matilde who’d befriended me on Facebook earlier that week was talking to the drivers, who’d arrived at the station fifteen minutes early to indulge in an extended cigarette break. The driver’s mate, one of those Argentines so garrulous he would ‘talk to a post’, as the saying goes, asked Matilde if she fancied riding up in the cab of the locomotive, and she asked if I could tag along. It was that easy.

So in the dead of night, I did something I’d always wanted to do but never liked to ask, and hauled myself up the three rungs on the side of the loco, walked along the narrow gangway and into the cab at the back of the engine. Apart from the driver’s seat on the right and the co-pilot’s on the left, there was only a little stool to perch on, so the drivers removed a metal panel from the engine and propped this on the stool and the engine to make a makeshift bench for Matilde and me. None of this was particularly legal, as is probably clear, but it was awfully simpatico, which is far more important.

The driver sounded the mournful horn while the co-pilot, a former beekeeper who got tired of getting stung and went back to the railways, set a small metal kettle on an electric burner and brewed up for mate (explaining that this wasn’t all that legal either, in case there was any doubt), and there we sat and sipped and chatted for two hours, the loco making its slow progress along a single track, cutting through the branches and the brush, its lights beating a trail through the middle of nowhere, owls flitting past in the headlights, as the driver blasted the horn at a skunk on the tracks, which shifted just before it got squashed, leaving its smell behind. The sun came up outside a town named after a dead president as the mate was sucked dry and I decided to dedicate this book to drivers Eduardo and Ángel, and everyone else who ever worked on the Argentine railways. This book is for them.